What is blockchain, really? (An intro for regular people)

You have probably heard the term “blockchain” mentioned in contexts as dramatically different as “a technology with the greatest potential…

You have probably heard the term “blockchain” mentioned in contexts as dramatically different as “a technology with the greatest potential for humanity” — Don Tapscott vs. “Either a Ponzi or pyramid scheme” — Washington Post. It has potential to be the former, and it can (and has been) used for the latter. However, it is important to understand the core principles of the technology without any bias to understand its full impact.

What blockchain is: A blockchain is an open database maintained by a network of independent participants who get paid in cryptocurrency (tokens) for their work. It is trusted, permanent, and public such that everyone can inspect it, but which no single user can control it. It is a protocol which allows for trustless, peer-to-peer exchange without a central authority. It can be used to build the internet of value, pre-programmed with smart contracts that are triggered automatically. Philosophically, it is also a shared vision of reality between all the participants.

What blockchain isn’t: The term blockchain isn’t limited to a single use case (including the bitcoin blockchain). It is also not an actual store of value but the accounting and transacting of value. E.g. you cannot put the actual value of real estate onto a blockchain, only who owns which properties and rules that automatically trigger the transfer of deeds should certain events perspire.

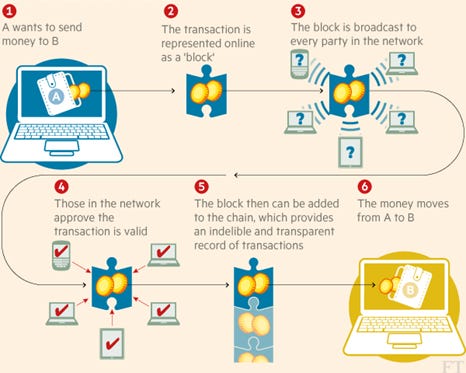

This and this Economist article are good resources for a more complete overview of the technology behind blockchain. This FT illustration is also a pretty good abstraction of the bitcoin blockchain:

It is important to understand that the blockchain is just a cryptography-based technology, and there are actually hundreds of different blockchains being built, differentiated by use case, developer communities, and governance. To understand why so many blockchains, you can listen to this A16Z Podcast or read this article. The gist of it is that each chain is designed with core principles that serves a very specific use case, which can make it very inefficient for other use cases. My friend, Joel and others wrote a good summary of the various alternative blockchains here. It’s important to note that many of the current blockchains may not be the popular choices in the future, but there are strong network effects holding each one in place.

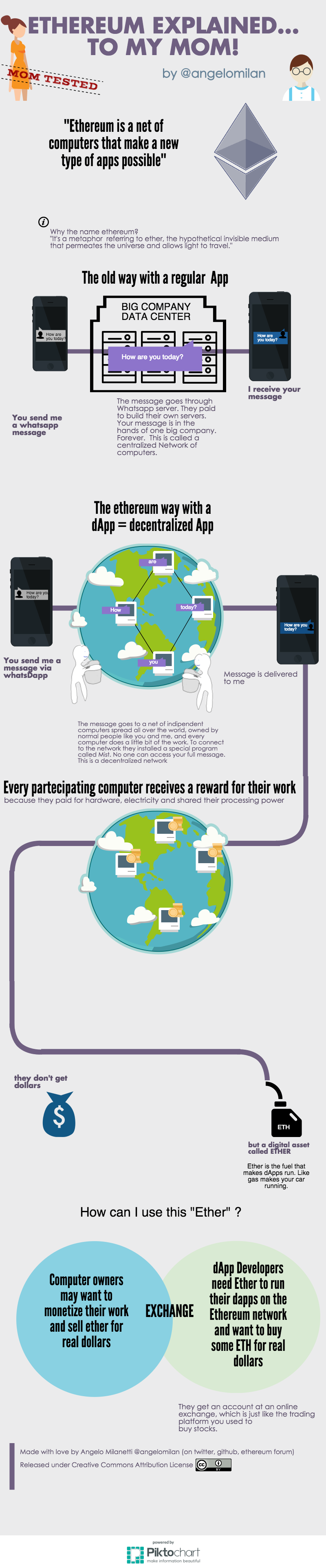

Perhaps the most well-known blockchain, next to the bitcoin blockchain, is Ethereum. Its use case is to execute automatic smart contracts in a decentralized way. Here is a good, simple explanation of how Ethereum works:

Another interesting blockchain use case to check out is STEEM, a decentralized media platform where users are paid by the network based on the value of their content creation or curation efforts to the community. An average good post with decent reach puts about $5–10 bucks directly into the author’s pocket. In STEEM, a content creator posts something, and people read and curate it (upvote, comment). When the content generates engagement, the STEEM blockchain automatically rewards the creator and early curators with a digital token called STEEM. Others can buy STEEM tokens because more STEEM = a more influential vote and higher ranking posts. You can also pay STEEM to the network to advertise your posts. Others can also buy STEEM tokens as an investment, in anticipation of the platform’s future growth. This bids up the price for STEEM and allows content creators and curators to get paid by selling their earned STEEM tokens.

The STEEM blockchain is perhaps a good illustration of a concept often referred to as “cryptoeconomics” or “tokenization of value”. To understand this, it’s important to understand that each blockchain is essentially its own economic system, where the value is captured as tokens. For example, Bitcoin is the token for the Bitcoin blockchain; Ether is the token for Ethereum; and STEEM the token for the STEEM blockchain. The economics behind blockchain tokens requires us to shed our understanding of how a traditional company works. A traditional company organizes value exchange between supplier (which can be itself) and consumer and captures the surplus as profit which is then distributed via cashflows out to the shareholders. It is on this expectation of future cashflows that the company is then valued. A blockchain network facilitates value exchanges directly between supplier and consumer at a cost to the network that is equivalent to the reward for recording (often called mining) the transaction. Those doing the work to record the transaction (miners) are paid in tokens directly by the blockchain protocol, and all of the value created is paid out to the network via tokens directly. To use the blockchain’s services, tokens must also be paid to the blockchain, so in that way, they can be like tickets to a fair. Additionally, the price of the tokens appreciates as more people buy into the limited supply (either for use or speculation); therefore, the value of the network increases when the network is expected to grow. In this way, the token can also act as shares of equity in the underlying blockchain. In essence, valuing a blockchain is more akin to valuing a monetary system (based on GDP and economic productivity) rather than valuing future cash flows. As the tokenization of value is a lengthy subject, and I’ve only just dabbled the surface, you can read more it, explained by those who came up with the idea, here and here.

Despite the technology’s uncertain future, most people who have studied blockchain can agree that the theoretical applications of blockchain technology, if realized, could profoundly transform on our society.

“With blockchain, we can imagine a world in which contracts are embedded in digital code and stored in transparent, shared databases, where they are protected from deletion, tampering, and revision. In this world, every agreement, every process, every task, and every payment would have a digital record and signature that could be identified, validated, stored, and shared. Intermediaries like lawyers, brokers, and bankers might no longer be necessary. Individuals, organizations, machines, and algorithms would freely transact and interact with one another with little friction. This is the immense potential of blockchain.” — Harvard Business Review

From Northzone’s perspective (and many investors would agree), the biggest challenge in assessing the potential returns from investing in blockchain technologies is the timing of adoption. There are some parallels to the adoption of the internet through two separate movements — centralized vs. decentralized — which are actually not so separate. There are also certain prerequisites for mass consumer adoption. In a series of blog posts after this one, I will walk through our thought process on how we approach investing into this space.