Self-Sovereign Health

Preface: I started this post six months ago and never hit publish because I never felt it was “done”. Six months later, it’s still not…

Preface: I started this post six months ago and never hit publish because I never felt it was “done”. Six months later, it’s still not “done” because health is such a complex topic, and I can only offer a sliver of insight based on my own journey rather than anything resembling comprehensive. With that disclaimer, I’m hitting publish anyway… because blog posts are supposed to be raw, personal, and only somewhat baked. Hopefully some of what I discuss will resonate with the reader.

A personal story

I have been lucky enough most of my life to have only had to marginally interact with the U.S. healthcare system — the occasional accident when I was young, but the rest of it is pretty routine. It wasn’t until I decided to have kids that I became a real “customer” in the system. I have two kids, one was born in one of the leading hospitals in Manhattan — the epitome of a private, high intervention health system, and the other was born in the NHS in London— the epitome of a public, low intervention health system. I had pretty serious complications in both instances, and luckily the babies and I are all fine in the end. The experience between my two births were polar opposites, yet both equally terrible. I didn’t feel like a customer at all, I felt like an object, having healthcare “done onto me” by many different parties, each with their own incentives and broken pieces of data, and no coherence overall. This next-level horrid customer experience, delivered by some of the best practitioners in the world, is what sent me diving down the healthcare rabbit hole.

The U.S. system was characterized by loads of highly invasive interventions, prescribed by experts doing what was best for me but often without a clear delineation of what would be my choice vs. what is necessary nor clearly explaining what the risks were:

Getting my “buy-in” was a burden to the doctors and nurses, and that was clear in the way they interacted with me.

After 37 weeks of a happy and healthy pregnancy, one of the doctors in my OBGYN rotation decided to begin a series of unnecessary interventions that escalated to some spectacularly bad outcomes. The first time I met her, she decided to dilate my cervix, without asking for my consent. I might have given consent but the big issues is that I didn’t even know if what she was doing was something I needed to give consent over or if it was a part of the standard practice. In addition to it being extremely painful, that day after I came home I began to feel very uncomfortable and then, my water broke, but my body was obviously not ready to go into labor yet. Then at the hospital, when my body wanted to take more time, the interventions escalated from hormonal induction to more manual dilation, nothing happened for 12 hours until my body basically went crazy and dilated from 10% to 100% in 10 minutes. For those of you unfamiliar with the process of labor, this is not normal. All of this lead to a massive hemorrhage that required me to get two blood transfusions and two plasma transfusions and might have ended in a hysterectomy if they couldn’t get the bleeding to stop. Luckily, none of this affected the baby directly and the bleeding eventually stopped after several more interventions. After it all, I remember distinctly hearing the doctor responsible say “thank god you delivered in a hospital, or we don’t know what would have happened”, somehow with no sense of irony.

Several years later, after I forgot all about the trauma, I was pregnant again with my second son. This time, for reasons no one could explain, I went into labor two months early while I was on a business trip to London. There, I got to learn all about the NHS.

The U.K system provided zero room for personalization, and the need to adhere to protocol greatly outweighed my need to understand the risks and the tradeoffs made on me and my baby.

I went into an NHS with some abnormal bleeding after 31 weeks of another happy and no-complication pregnancy, but I was sent home with nothing after they did a couple of routine exams. Then I went back with light, regular contractions and bleeding and was kept overnight with some acetaminophen and sent home again. The next day I came back with regular intense contractions and was told they couldn’t give me anything to slow my contractions until the baby was basically already coming (???). I delivered my second son at 31 weeks, and pretty shortly afterwards had another massive postpartum hemorrhage, but this time I wasn’t given a blood transfusion because I was below the NHS threshold for needing one, so I spent a couple of weeks feeling extremely weak and dizzy.

In both cases, I had no champion to gather all the pieces and fill in the gaps between the countless handoffs from care team to care team, and I wasn’t in the position to be able to do it myself. In both cases, it was hard to cleanly separate the positives vs. the negatives of each system as well as the causes vs. the effects of the intervention / non-interventions. I ultimately needed to trust in the expertise of my care teams, who I know was trying their best, but they are still constrained to and operating within a system that I know is so broken.

There was one microcosm where my experience was different, where the system felt like it was working and our incentives were aligned. My youngest was born prematurely, so he spent a few weeks in the NICU in the NHS. In there, there is so much data being constantly generated and observed, and as obsessive parent of a premature infant, I became a walking data repository for him. (I don’t recommend this level of data obsession for any parent by the way). The mean, median and standard deviation for his vitals, the names and schedule of all his medicines, when and how much he was feeding, the color and frequency of his bodily functions, and his every tiny developmental milestone — I had internalized it all. I joined the daily handoffs between the nurses and the doctor teams, and they began to rely on me for my input in gaging his progress.

It felt empowering to be the owner of all this data and understand exactly when and how to escalate anomalies; it also felt good to not freak out every time the heart rate/oxygen monitor beeped.

We addressed his acid reflux early on, dealt with his high blood-calcium levels, transitioned him off of oxygen very quickly, and when he learned how to feed independently, he was ready to be discharged. He only spent a record of 4 weeks in the NICU (which I’m told is very rare for a 31 week preemie). Overall, I felt that I helped significantly improve the standard of care for Dylan by proactively participating in the data stewardship, and the NICU specifically had a good system such that it allowed me to play that role. The same can’t be said about many other medical experiences. The NICU was this tiny little microcosm of data where I spent 8–12 hours per day talking to the doctors and nurses, this was the cost of maintaining all this data for my son. Still, disappointingly, at the end of his stay, all of the data was just thrown away, buried deeply within the vaults of the NHS in handwritten notes. We were cut off from the microcosm as soon as we were discharged, and my current pediatrician has only a slight glimpse into that entire journey, in the form of a discharge report, which took the NICU doctor hours to put together, that she maybe looked at once for 5 minutes. Other than that, the most important data repository for my baby was me.

My youngest, Dylan, born 31 weeks and 5 days

What’s the problem

I always knew healthcare was so broken, but my experiences with childbirth made it that much more vivid. I spent some time trying to understand how my experiences applied to the broader topic of healthcare, and many of the issues are the same. If you’ve ever had any kind of health issue, you’ve probably been both tempted to and explicitly told not to google your symptoms. Today, there seems to be a conflict between a consumer’s role in her own health versus an expert’s.

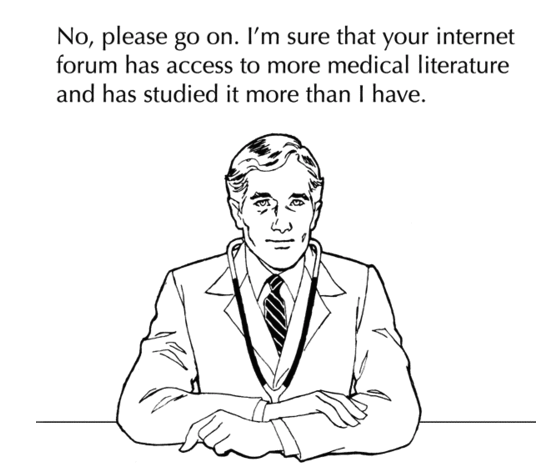

Credit @trishgreenhalgh on Twitter

Why does this conflict exist? Why is there such a thin line between “thoughtful consumer” and “hypochondriac” — digging deeper, it comes down to data and incentives.

Consumer-generated health data is lacking and poorly curated. Living with a health condition is an incredibly lonely experience. Although we know that there are probably thousands of people in the world who have experienced similar health issues as us, it’s still impossible to find them in our “connected” world. General social media channels are not the best forums for sharing health issues, and Google, though it has done wonders for general education, falls extremely short when it comes to health data. What exists currently are fragmented anecdotes from outdated forums posted by other desperate consumers, spread out across time and space, looking for answers but mostly getting emotional support at best and hypochondria at worst. (It was definitely hard to fight the urge to Google everything with my two kids). The curation algorithm that runs Web 2.0 fails miserably in highly specialized genres such as health.

Dr. Google.com

More reliable publishers exist to offer basic guidance, but they are still stuck in the Web 1.0 format of 1-to-many broadcasts, offering user experiences reminiscent of Craigslist. There are some companies like The Mighty and Patients Like Me innovating in this space; I am very excited to see more.

In addition, good individual health data just frankly doesn’t exist in the U.S., digitally at least. Medical experts are only able to access thin slivers of your entire health data trail — in the form of limited paper medical records, labs/tests/scans done on you at that point in time, and what you can remember to communicate to them on the day of your visit. Most of the data management is analog and broken, so even when it does exists, it’s not where it needs to be when it needs to be there.

Nearly one-third of individuals who went to a doctor in the past 12 months reported experiencing a gap in information exchange — dashboard.healthit.gov

Based on only thin slices of data, only population-wide comparisons are possible, but we know that health is highly personal. It always seemed odd to me that some doctors advise against comprehensive testing like full-body scans because it triggers a lot of “false positives” (how can more data be bad???), but then it occurred to me that without an understanding of the linear progression of your own baseline data through time (longitudinal data), the results can be useless at best and falsely alarming at worst. Longitudinal health data is currently prohibitively expensive to build and impossible to store. Many hospitals now are adopting electronic health records (EHR); companies like Ciitizen, Particle, and ZocDoc are pioneering consumer-led approaches for data collection; and increasingly more people are using wearables and storing their data with Apple Health. However, when you think about how much data we have for systems as complex as our bodies and our mind vs. something like our browsing behavior or shopping activities, I’d say we are only at the very very beginning of the data collection exercise.

Last, in the practice of healthcare, the responsibility handoff isn’t clearly delineated between the consumer and the various healthcare providers. Consumers are not empowered to be proactive champions of their own care, in fact, sometimes there is a visible conflict. For example, our healthcare system is set up such that the doctor gets very little leverage, and most of their work is done with each patient in person. As the doctor is incentivized to see more and more patients, the visits themselves don’t change. Each interaction is composed of patient education, data collection, diagnosis, and treatment, and the time spent educating the patient often comes at the expense of the other tasks or the doctors ability to treat all her other patients on time. Some OBGYNs actually discourage the use of doulas whose sole job is taking the patient’s perspective because it makes the doctor’s job harder. The spread of medical misinformation thanks to Dr. Google probably makes this conflict even more visible.

https://www.thummimng.com/most-common-patientdoctor-conflicts/

Health data is complex, and much of the pattern matching should probably be managed by experts. However, there are roles within the data value chain that are best performed by consumers, who have the most incentive to do it right (and also happen to spend all their time with the data subject). Consumers can be stewards and aggregators their own health data. They can also be taught to recognize signals for escalation. They are not empowered to do that now, and this handoff is so broken. It’s mostly done in the format of a few vanilla health history questions that care providers spends a maximum of a few minutes interpreting at the beginning of a visit. Escalation happens only at severe malfunctions — this is why we have a “sickcare” system vs a healthcare system.

“Wellness” vs. “Sickcare”

I am not a proponent of self-diagnosis, and I think swearing off of the advances of modern medicine is harmful and stupid. But I also think some of these health conspiracies arising from distrust of the system are direct results of our lack of self-sovereignty in relation to our health. On top of the growing skepticism, the reactive attitude about our health forces us into being overly reliant on reactive interventions. The system trains us to be objects rather than empowered consumers.

https://www.thummimng.com/most-common-patientdoctor-conflicts/

Consumers in China have long been taking health into their own hands by relying on the principles of Chinese Traditional Medicine (CTM). I was born in China, and I grew up with my mom, aunts, and grandmas always nagging me to moderate the amount of inflammation in my body by avoiding specific foods and to increase my Chi by taking certain herbs. I always used to dismiss the advice as old wives tales.

Regardless of whether or not you believe in the methods of CTM, what I’ve come to realize is that the most important thing about CTM is probably not the specific curative properties of certain herbs or tonics but that it provides a framework for people to constantly observe their own body and a way to proactively manage their own health — It makes them tune in.

Within some healthcare categories, western consumers have already taken the proactive role in their care. Categories such as nutrition, dermatology, optometry, and orthodontics were the first to shift, and companies in these sectors have had a lot of success speaking directly to the consumer, with the help of medical professionals. I believe many more categories will start to shift in this direction, such as physical therapy, fertility, developmental pediatrics, chronic disease management, and mental health. Many startups are already building in this space (Kaia, Natural Cycles, Kindbody, Thirty Madison, Shine), and I’m very excited to see more. Overall, I’m super excited to see many more companies using technology to empower us as healthcare consumers while leveraging our medical professionals, and I will be spending time looking for investments in this space.

I’ll end with this: a pretty cool example of how nuanced the topic of nutrition has become when empowered consumers start to take health into their own hands: